How strange that this exhibition featuring artworks, photographs and memories created in the aftermath of war should take place as the very spectre of war should return to haunt us in Europe once again. And how appropriately fitting that this exhibition should take place in the Barbican Centre on its fortieth anniversary, an iconic architectural space created on a former bombsite from World War II. As the catalogue states “an opportunity to see Brutalist works in a Brutalist space and, extraordinary postwar art perfectly sited in an iconic postwar

edifice”. The exhibition explores the artistic mood in the aftermath of the devastation of major conflict. There is an ambitious scope as the curators of the exhibition have done a good job of incorporating not only painting and sculpture, but also photography, ceramics, architecture, industrial design, and an experimental immersive film installation by Gustav Metzger. This diversity of artistic disciplines as well as the inclusion of lesser celebrated artists is both the triumph and strength of the show. There are the works of many new or overlooked artists to discover. as the curators have sought to redress the balance of artists who have been previously marginalised or excluded. At the same time there are some glaring omissions. A painting or two by Peter Blake from the period for instance wouldn't have gone amiss. As one walks through the Barbican's galleries we are taken on a journey of the formal elements and techniques of art and design. There are some wonderful textures in the sculptures of Paolozzi, the painters who forged a reputation at the time such as Alan Davie, Franciszka Themerson, the heavy impastoes of Leon Kossoff and Auerbach with the gorgeous nature-based collages of Nigel Henderson. We are always led to believe that this period in history was drab and deprived of colour but this is contradicted by the vibrant paintings of Magda Cordell and Anwar Jelal Shemza. Form is taken care of in the sculptural ceramics of Hans Coper, Lucie Rie and the sculptures of William Turnbull. There are also the works of the artists working in severely straitened circumstances but with a sense of hope, and an eye to the machine and space-age future with the burgeoning glamour of consumerism such as Richard Hamilton. I really enjoyed the sharp contrast/mix of those artists working in abstraction against those clinging staunchly to figuration - Bacon, Freud, and two exquisite lesser-known Hockney's. The revelations about the bullying and abuse against his talented artist wife Jean Cook by John Bratby were sad, but no surprise given that most artist wives of the time and earlier were forced to abandon their artistic careers to support their more celebrated husbands and the duties of child rearing. Another surprise thrown up by this exhibition was the secret cross-dressing life of art critic Lawrence Alloway captured in a couple of paintings by his lover Sylvia Sleigh. A healing aspect and antidote to the times and bomb-ravaged environments are the life-affirming photographs of Bert Hardy, Roger Mayne and Shirley Baker of children adapting to circumstances and getting on with life as they are wont to do, seeing the bomb sites as new environments and opportunities for play instead of destabilisation and death, like certain war-waging adults.

Sunday, 12 June 2022

Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945-65

Gillian Ayers - Break-off, 1961

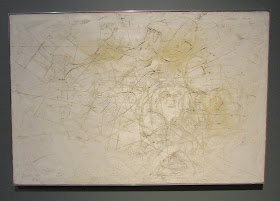

John Latham - Full Stop, 1961

David Hockney - My Brother is Only Seventeen, 1962

William Scott - Blue Still Life, 1957

No comments:

Post a Comment